The Yield Curve and the Fed

by AMG

On Wednesday of this week, the FOMC released the minutes from their October meeting. The committee reiterated that they are likely to begin tapering the asset purchases of QE3 "in coming months," a phrase that sparked a sell off in longer dated Treasuries. However, both the minutes and recent Fed speakers have emphasized the likelihood that short term rates will remain low for an "extended period" and perhaps well beyond the stated unemployment thresholds.

So, the market is being told that short term rates will stay low, but that long rates may soon drift higher as the Fed slowly reduces its presence as the market's overwhelming buyer. There are plenty of opinions on both sides (for both higher and lower rates), but regardless of what you think will happen, the market is speaking rather loudly. The curve is getting steeper, which we have seen through most of 2013. The interesting thing, though (especially for the banking industry), is where the market is getting steeper. Check out this chart from Bloomberg that shows the spread between the 5 year Treasury and the 10 year Treasury:

The chart goes back to the early 1990s, giving this recent move some context. We are at multi decade highs in this absolute spread. Also, keep in mind that since we are such low nominal yield levels, the difference in percentage terms is huge.

So, a steeper a yield curve is good for banks, right? In general, the answer is a resounding YES. This was especially true over the summer when the curve was steepening fairly dramatically between 2 years and 5 years. Bank assets tend to reside closer to the 5 year portion of the curve, while liabilities tend to price off of much shorter durations. Banks were finally able to invest some of their deposits in the belly of the curve and receive some modicum of return.

However, a steepening of this degree this far out on the curve is not so easy an answer. To see why, let's take a look at what the yield curve is telling us.

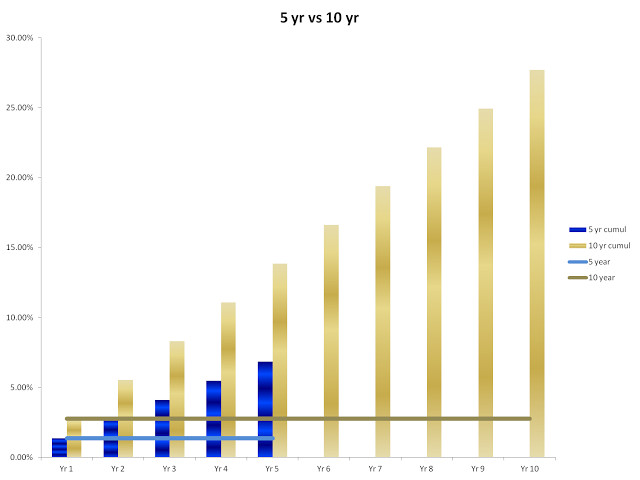

This morning, the 5 year Treasury had an annual yield of 1.37%. The 10 year Treasury had an annual yield of 2.77%. While the spread of 140 basis points does not seem that dramatic, let's compare an investment in the two instruments, summarized by this chart (note that for clarity this is oversimplified, ignoring the time value of money and reinvestments, both of which would make the difference even larger):

At the end of 5 years, you will have earned 1.37% * 5 = 6.85% on the 5 year. You will have earned 2.77% * 5 = 13.85% on the 10 year. That is a huge gap to overcome. Over the life of the 10 year, you will earn 27.70%. That means that at the end of 5 years, you would need to earn at least 4.17% in years 6 through 10 to break even (again, ignoring time value and reinvestments). So, if you are buying two 5 years instead of 1 10 year, you are betting that the 5 year rate will increase by 280 basis points in the next 5 years. In other words, that rate will more than double.

What are the implications of this for banks? I can think of many, but here are the biggies:

- The yield curve is BEGGING you to add duration, especially if you happen to think rates will stay low for a long time. Even with QE tapering, a fed funds rate anchored at zero for the foreseeable future will keep a lid on any dramatic jumps in the 5 year, right?

- The market, though, is telling us to watch out for a quick spike in rates. The Fed may keep those short rates low for a long time, but once the increase starts, it will have to be fast and violent for this steepness to make sense. How can you hedge against this?

Overall, I fear that this reshaping of the curve, while good for earnings, will only add to the already high levels of interest rate risk in banks. This particular steepening entices banks to go out even further in bonds and loans, and makes some of the liability hedging that has gained popularity (namely forward starting liability swaps) more expensive. Making guesses on future rates is always treacherous, but is exponentially more dangerous as you make them further out on the curve. Be careful in how you construct your balance sheets, and as always, let us know if we can help.